February 2022

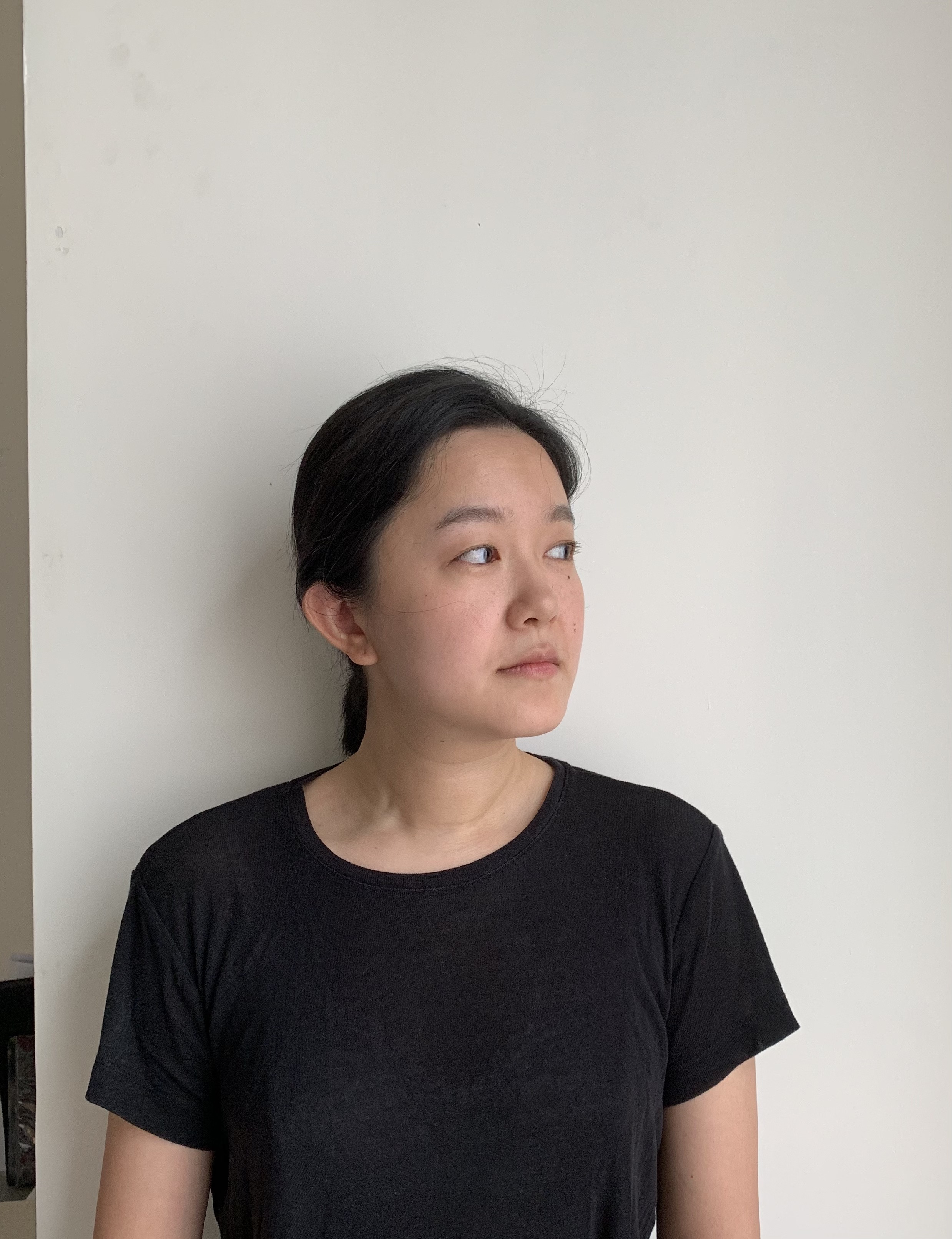

Chang Qu

Lo-fi home mix

A man abruptly shouting “lunch!” in the opening scene of Phung-Tien Phan’s Girl at Heart (2020) is just about the only indication of time in the video – or any of the three videos presented here, for that matter. Swiftly, the video takes a cheerful pace, intermixing photos of burning luxury sportscars with footage of a chef scoring squid from what seems like an Asian cooking show and a man sipping red wine in a cosy bistro, sound-tracked by upbeat erhu Chinese folk melodies paired with rapid chopping noises. Then it transitions to a wobbly handheld camera shot, tracing modern mouldings inside a clean, white-walled apartment. In a typical family kitchen, Mad Men plays on a laptop next to the stove. Accompanying the sizzling sound of tofu frying, Don Draper leers at colourfully dressed women on the street. Next, it goes to a mantelshelf, and outside to a boulangerie. It rotates past the window, the city spinning, the sun radiating. Following the light, it continues to wander through the city, a park, an empty street. Finally, it finds the artist, carrying a duffel bag that says “murder”, walking down a high street while in a stand-up-comedy-style voiceover she speaks about vintage fetishes and some of her mom’s crude jokes. The frying sound comes back. A Vietnamese pop song by Min cuts in. The end.

Time and place are confusingly mixed; footage is edited in a non-linear manner, as if it could be played on an infinite loop. Meanwhile, a sense of coolness and a middle-class lifestyle are subtlety and consciously staged. Whenever I watch Phan’s videos, I feel like I’m immersed within a lo-fi playlist, or what the late Mark Fisher termed “hauntological music”. I am a fan of the genre, really. The loosely knitted musical fragments sampled from a blend of old and new tunes, mixed with distortions and hisses from an analogue synthesiser, scenes taken from late-20th-century films, TV shows and commercials, at a chill, rhythmic pace just relaxes me. Here, one’s attention is constantly dispersed and stretched by overwhelming musical/cultural references. In Phan’s videos, The Beatles, The Strokes, Kanye West, Post Malone, and Min blur any sense of era indicated by musical styles. From time to time, footage is played in slow-motion, further insinuating the sense of being stuck or befuddled.

Hauntological music points to the return and random assembly of past musical memories into a new cultural sphere. It is a “new” reality constructed and thus perpetually haunted by empty nostalgia. Phan’s jokes about rich men’s vintage fever in Girl at Heart play precisely with such anachronism and the loss of historicity as a trending aesthetic. In her mixing of video and audio slices, music exudes a powerful materiality as an essential fabric of the described reality. In Half Moon (2019), Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode” is paired with footage of the artist’s Vietnamese father walking in an Asian restaurant, the music transforming his nervous march into a hip catwalk stride. Meanwhile, sluggish, eerie electronic beats often accompany angled shots of apartment interiors, accentuating a certain ghostly nature of such spaces. Music haunts, yet this state of being haunted has nothing to do with horror; it is more hypnagogic and ethereal.

Amidst the hauntingly disorienting music, the sense of space is as distracting as the temporal experience. Simon Mielke, a shy, skinny white male, roams endlessly through shopping malls, restaurants, apartment blocks, and domestic spaces. With him as the main character in her videos, Phan mixes spontaneous shooting with scripted filmmaking, living with acting. Here, the transitory nonplace – a term coined by anthropologist Marc Augé to describe spaces of late modernity that have no cultural specificities such as airports and motorways – seems to spread from the classic venues of transience into the private sphere. Increasingly standardised familial ideals render intimate spaces as flat and as modular as hotel rooms and supermarkets.

In Actress & Actors (2019), another of Phan’s videos, two men stroll through a posh residential area while an audio clip extracted from Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee and Cigarettes (2003) plays as the score. One listens to the comedians Roberto Benigni and Steven Wright, struggling with language differences, speak nonsensically about enjoying coffee. The conversation ends with Benigni saying, “Very good. I don’t understand nothing. Yes.” Yes, it is precisely the incommunicability, the irrelevancy, the lack of a temporal or geographical anchor that puts one in a vacuum, in a state of weightlessness; that relaxes.

If the disappearance of cultural time has engendered a “strange hybrid of [the] ultra-modern and the archaic See: Mark Fisher's book 'Capitalist Realism', chapter one”, Phan’s videos are, in this sense, an imitation of the audio-visual language of such disorienting hybrids. On one hand, her moving images are reminiscent of ’90s home videos in which the shots are awkwardly crooked and the image is incurably grainy. On the other, they share an affinity with the TikTok and YouTube generation of short, choppy videos in which vloggers scurry about pointlessly and obsessively from café to café, one bourgeois interior to another, in a flat and global web of internet data flow. Distancing itself from the stereotypical lo-fi aesthetics exemplified by a visual hodgepodge of Japanese anime, ancient Roman sculpture and architecture, tropical landscapes and the digital visual effects of the ’90s, Phan’s work plays with the compositional grammar of the lo-fi musical trope with analytical precision and parodic absurdity. Her videos both re-enact and tease the social media image production that has been chaperoned by the neoliberal market economy. If lo-fi music and aesthetics are pastiche of cultures past, then Phan’s works can be seen as pastiches of the pastiche.

A plethora of possible narratives – such as diasporic experience, female labour and motherhood, the standardised middle-class lifestyle and late capitalist production – can be found in Phan’s seemingly chaotic blends, though none of them bothers to take centre stage. Whether the videos are made to critically examine the poorly constructed reality we are situated in or to further confuse and mesmerise contemporary viewers’ already-shattered attention spans is unclear. The artist is, at times, embodied by the little girl in Half Moon, joyfully messing with the laptop keyboard, interrupting the flow of music. But in other moments, like when she sits in a car, blowing out virtual smoke that reads “Maybe cause I’m a dreamer and sleep is the cousin of death”, she’s deeply melancholic. Of course, this doesn’t really matter. Because in the next second, a “new ‘new’” pop ups and replaces any thought that lingers.

Chang Qu is an independent curator and writer based in Hong Kong.