June 2022

Olamiju Fajemisin

Metapainting

Peering at the 13-inch screen of my laptop, I tap the “increase brightness” button until it reaches the highest setting and squint. Using my fingers to pinch and scroll, I zoom in on high-resolution images of paintings by Srijon Chowdhury so that I might imagine viewing them to scale. The works, all oil on linen, swallow my screen as I search their surfaces for traces of reason amongst the artist’s preferred motifs: Chiaroscuro, botanical devices, and naturalism command the scenes of this painted, metaphysical dimension. The images are wont to suggest a religious interpretation, though this is quickly realised to be an illusion projected by the sheer banality of each scene as Chowdhury imagines the contemporary through his mythic, Mannerist style. The artist was raised in the US and Bangladesh, where he was born in Dhaka to a Bangladeshi father and an American mother, and now divides his time living and working between Los Angeles and Portland, Oregon The simultaneous banality and significance of these details exemplify the question of subversion in Chowdhury’s work.. One might also describe his style as coming after miniature, or Mughal painting, which developed in the Indian subcontinent as royal patrons encouraged painters to assume the principles of the concurrent European art, producing highly detailed, pictorially flat images of histories across the personal, moral, romantic, religious, agricultural, royal, pastoral, mystical ….

Across these six selected works (all 2020), Chowdhury’s palette exudes an emotional span which slips between excitement and despondency. A vibrant cast of shades evade being sucked in by the muted dregs of grey-brown-black-blue in Medieval Tapestry. An elegant pair of hands cradles a rectangular device which shows a two-dimensional patchwork image of an Edenic, verdant dreamscape. Going anticlockwise from the top right: A pink unicorn rests in a ruby-red pasture; a Rorschach-like, highly detailed fern is surrounded by a border of vines and berries; against a black background, concentric circles of stemmed flowers spiral around a central white bloom; and more stemmed flowers sprout forth from a green lawn. The colourful light emanating from the handheld screen only just illuminates the person’s fingers, then soon dissipates into cold nothingness. Chowdhury takes his inspiration for abundant natural imagery, as seen here, from the land surrounding Asgar Ali Chowdhury Jame Mosque, built by the artist’s great-great-great-grandfather. Located just outside of Chittagong, on the southern coast of Bangladesh, the building is in the Mughal architectural style, which, like Mughal painting, incorporates delicate ornamentation and allusion to botanical forms. This rich historical and personal context outshines any potential significance of the handheld communication device: The phone is not the subject of the image, merely a proxy tool, a looking glass through which to observe into the beyond, its proxy function to observe the secret garden. However, this imbalanced significance is immediately confronted by Black Mirror, a work of similar ilk and size, showing what most would recognise as a phone, though here it appears as an over-elongated, black tablet, that seems to float between two frail hands. With this inversion, the suggestion of realism becomes confused with relatability. In the long dark screen – a literal black mirror – we see the reflection of a woman gazing at the device, and though she is rendered in “true” tones, if heavily distorted, her sense of place and reality is immediately unsettled by the tenebristic red background surrounding her in which the artist explores symmetry amongst a scattering of flowers. (This peculiar all-red background is also seen in Horse Running: Stemmed flowers and weeds, also red, are whipped around by the movement of a fleeing horse, almost entirely out of frame. We see only one of its legs, lifted and poised mid-gallop, surrounded by a sheer ether.)

Despite their varying interpretations, Medieval Tapestry and Black Mirror represent an important convention seen in Chowdhury’s work as early as 2015: creating a frame within a frame. Whereas the artist usually creates this effect using winding, thorny vines, here the disembodied hands protect the boundary between inside and out. This idea is seen most clearly in A Prince of this World, a slightly larger work than the other two, which shows a winged humanoid figure wielding a scythe and stepping between a number of solemn faces that seem to emerge from between the fibres of a fleshy, womb-like realm. The scene is bizarre, by far the most abstract of these works. The figure’s wings have eyes, and it is hard to assess her aims. Nonetheless, the sequence is entirely contained within the safe grasp of a pair of sallow hands: The thumbs overlap at the base of the canvas, providing a foundation from which the fingers extend upwards, arching over, then finally meeting at the top. It seems to be a mythic vignette – one part of a much larger tapestry not yet woven.

The critic Dean Kissick, who has sat for portraits by Chowdhury on more than one occasion, remarks in the conclusion of a statement commissioned for the artist’s most recent solo show at Ciaccia Levi, Paris, “I’ve heard moths are drawn to the light, because they sense a darkness beyond it, on the other side, far blacker and louder than any we have known.” This disquieting, relativistic metaphor suggests a major theme of this work, representing the tension between the oblique forces of light and dark, or life and oblivion – an archetypal sentiment through which Chowdhury transposes visions of a seemingly neither personal nor collective heritage, causing crises of alienation in both the subject and the viewer. Sad Boy shows a hollow-eyed man walking across the foreground of the image, ignorant of the fact that he is being watched from behind by the titular Sad Boy, a child with a sunken face and an unsettlingly patient gaze. The two characters are ostensibly separated; though it is not entirely clear by what, it seems they are placed on opposite sides of a window. Their relationship remains unconfirmed as they become almost lost amongst the stifling, murky hues. There are few, if any, reliable markers of depth perception, and to further confuse the scene, ghostly grey shadows swarm the background, like columns of smoke without fire rising in natural forms.

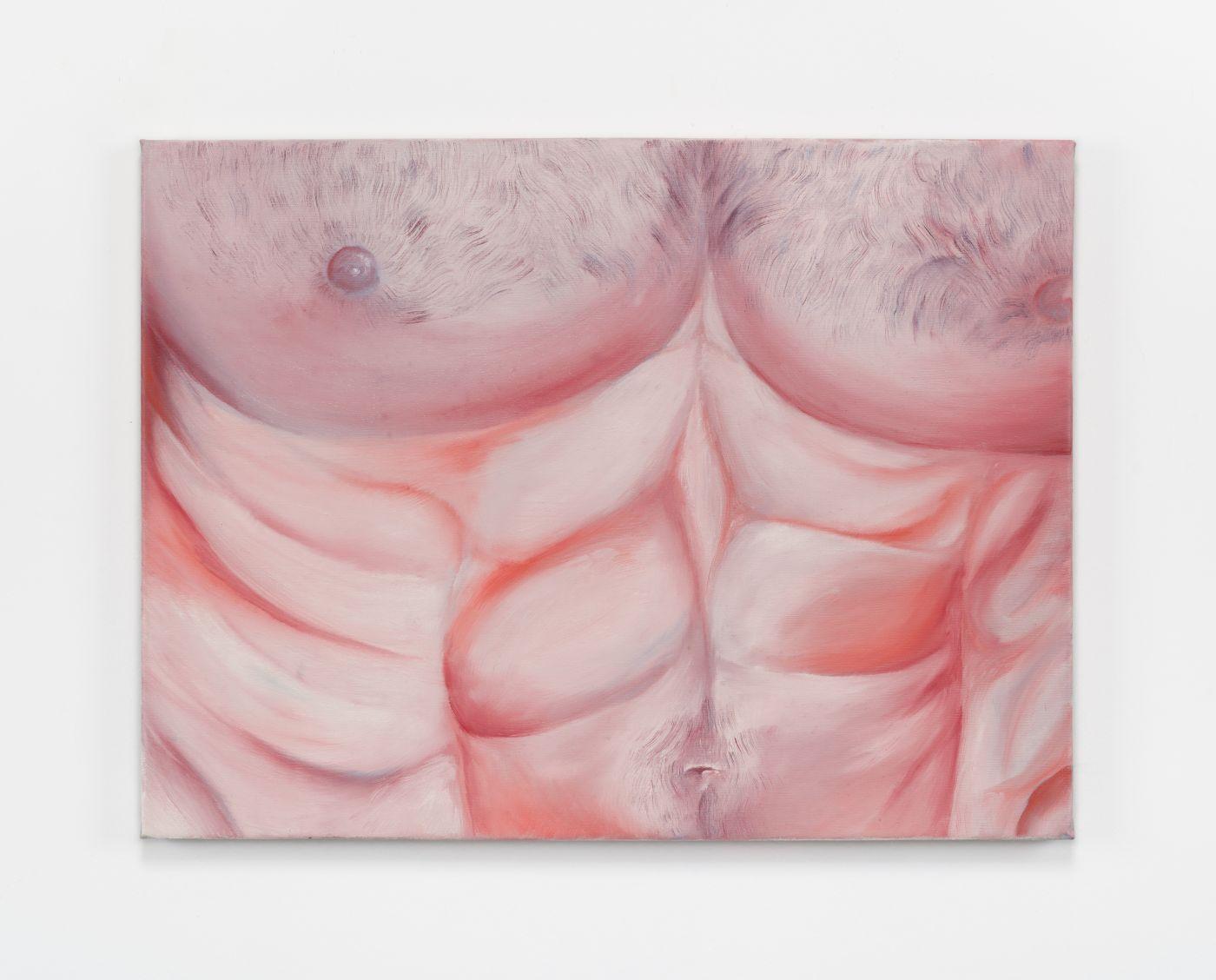

Beyond explorations of colour to literal, semantic ends, works like Torso exemplify the artist’s technical ability, a skill which is perhaps sometimes lost amid the myriad of details and symbolisms to ascertain. This aptly titled work measures at a little under life-size 45.72 by 60.96 centimetres, to be exact and shows a man’s chest and upper abdomen. Using a limited palette, Chowdhury invites scrutiny of this man’s physique, confusing the paths to sensuality and voyeurism as deep pink contours line his abdomen and twisting obliques. Muscle pulls below the surface of the skin as the torso struggles and flexes, quivers perhaps. The body appears tender, if hurting. It is not quite the Passion of the Christ, nor is it a naturalistic masculine ideal. Well-learned in the techniques of the Renaissance-era painters he is clearly interpreting – namely cangiante (working with few colours) and chiaroscuro – Chowdhury produces an image which is indicative of the ambiguous emotional effect realised throughout many other of his works. His actions are almost paradoxical, as he toys with the broad historical and international conventions of painting in a niche, concentrated and hermetic exploration of recurrent formal and conceptual motifs. By consistently reconfiguring ubiquitous art historical and contemporary symbols, the artist begets a new corollary for painting in the globalist era.

Olamiju Fajemisin is an independent writer and editor based in Berlin. She studied at the Courtauld Institute, London. Her criticism appears regularly in frieze, Artforum, and Flash Art, among other publications. She is the copy editor at Spike Art Magazine and a contributing editor of PROVENCE.