presented by Topical Cream

For the next year, Topical Cream is inviting authors to contribute a series of essays, interviews, and exhibition reviews featuring artists from the Liste Expedition universe.

September 2023

Olivia Rodrigues

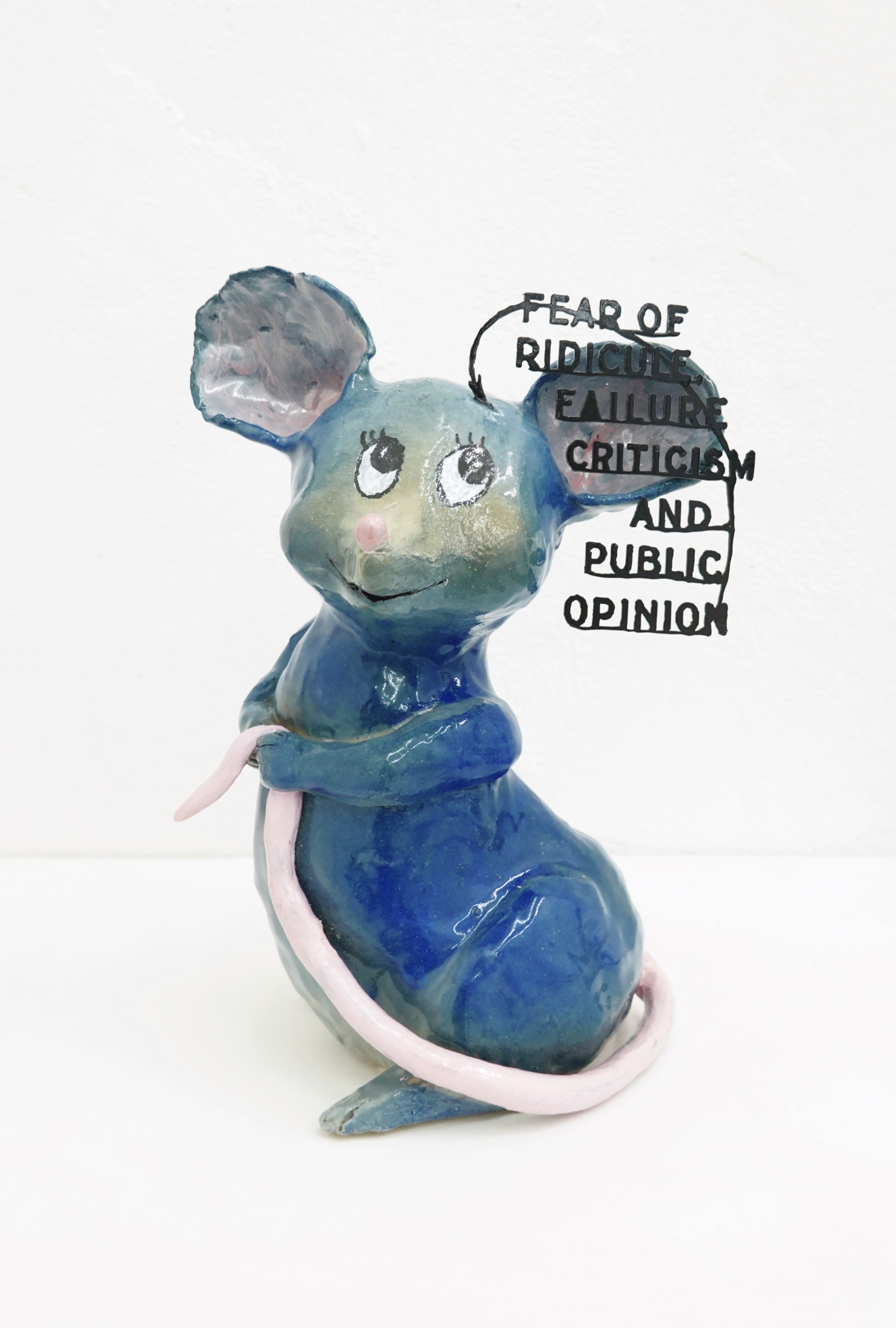

Cassidy Toner Bets Big

Ninety percent of gambling addicts quit right before they are about to win big. Or, at the very least, that is a lie that taunts the victim of sunk cost. A gambler straddles time: nostalgic for the past, bereaved of the present, and defiantly bullish about the future. They are distracted. Beyond optimism, the gambler maintains a blinding sense of possibility which—for brief moments of suspense—eclipses their present. This three-layer timeline motors each bet, constantly upping the ante.

It’s this orchestra of past and future that also propels someone like Cassidy Toner to wager her life and labor against her art world audience. When critic Paolo Baggi wrote about the Baltimore-born and Basel-based Toner, he noted that repeated bets parallel the repetition of a bad joke. This tactic appears in her series of objects Let me know how it turns out (2014–2022), where she plays with her odds by partially scratching off lottery cards. Rather than break the anticipation of what numbers lie underneath, the top layers remain intact except for small scenes inscribed by the artist. Among them are a man sitting on a stool, looking so intently into a pair of binoculars that he is about to slide off; a detail of an Ad Reinhardt cartoon; and two skeletons kicking back and hanging loose at the beach. With the frames a few inches larger than the cards themselves, these works supercharge their material against the gallerists and institutions that surround Toner. In the cost-benefit analysis of the cynical dealer, these lotto cards might be worth more as objects than artworks. In subject and material, Let me know how it turns out places the artist, dealer, and audience all as the gambler who determines themselves to failure. The late theorist Lauren Berlant termed this unfaltering insistence on the world: humorless comedy, in which the joke dissolves and is replaced by a subject’s mode of being as simultaneously imposing, undone, and helpless.

July 2023

Jennifer Teets

Luzie Meyer’s Cyclic Indirections

I first experienced Luzie Meyer’s work in 2019 at CACBM, an independent space run out of the rear of Galerie Crèvecoeur in Paris, where she performed Spilt milk is past recalling (2018), a humorous tale of spilled milk that uses a timed beat to sway and lead the reading. There was something in the nonchalant, ad hoc character of the work that drew me in—albeit the magnetism of its tongue-in-cheek philosophical references that alluded to something larger. Meyer works with film, video, photography, and performance to create visual gestalts in which the quality of the medium also defines the way the narrative is conceived. Feminist Marxist theory, literature, and film history infuse her practice with angles, perspectives, and “situatedness” as a means to an end: a way to visually document and simultaneously upend the model of the world as we know it.

May 2023

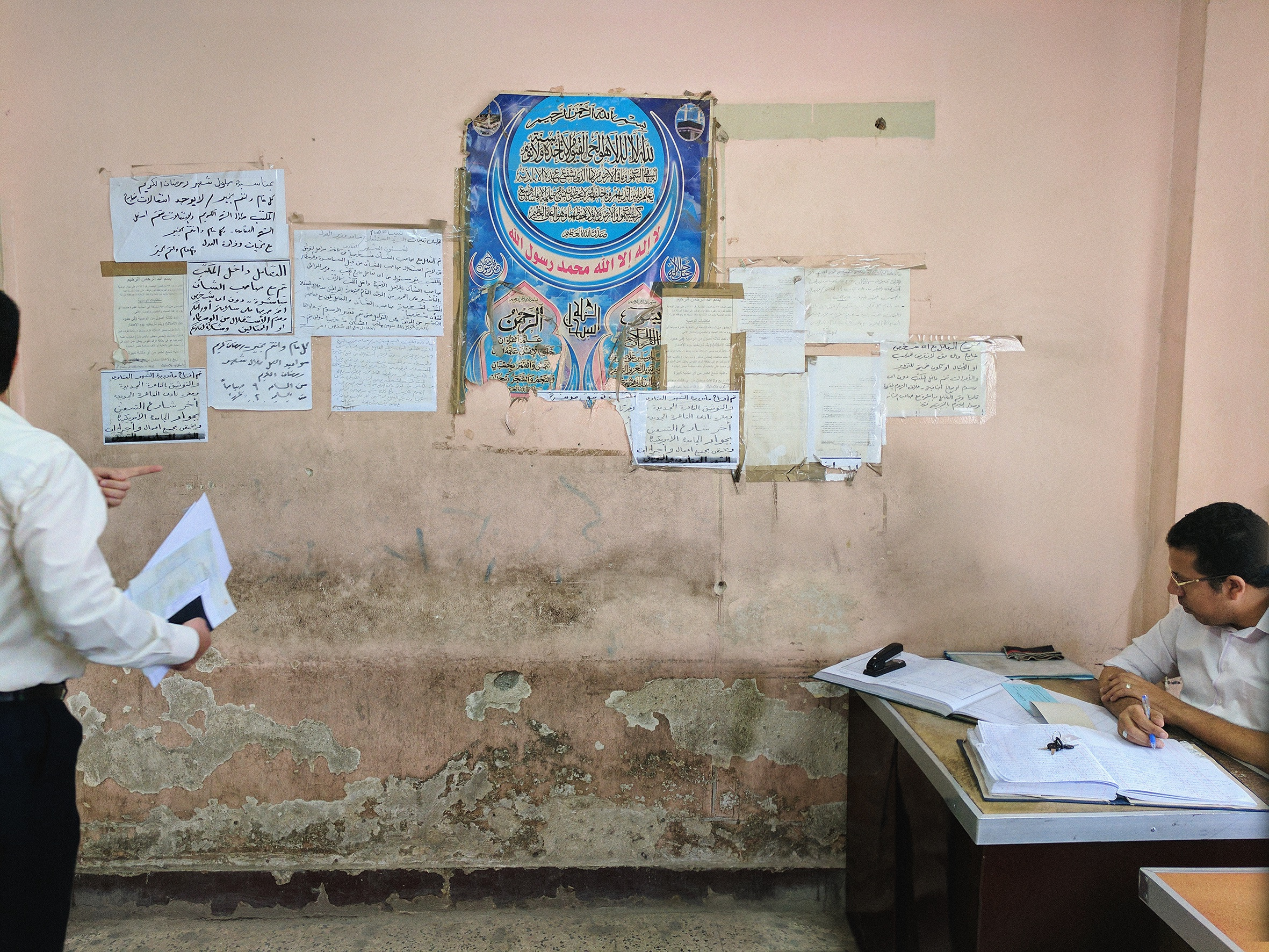

Isis Awad

Changing Cityscapes and the Romance of Bureaucracy: An Interview with Maha Maamoun

Maha Maamoun is a Cairo-based Egyptian artist, curator, and publisher. By playfully and intuitively making images and videos that weave together footage ranging from found YouTube clips of the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution to excerpts from bootleg copies of popular 1950s Egyptian films, she shares stories about common visual culture from an uncommon perspective. One recurring theme within her practice is nature, specifically how it’s seen and interacted with from within the dense metropolitan context of Cairo. Her film Shooting Stars Remind Me of Eavesdroppers (2013), for example, functions as a visual study of the flora and fauna in a public park, soundtracked by a couple’s intimate conversation over a picnic, while her photographic series Cairoscapes (2003), discussed in this interview, investigates the role of (artificial) nature within urban space.

When I called Maamoun, it was the first time we had connected since seeing each other in Cairo in 2016.

March 2023

Elizabeth Wiet

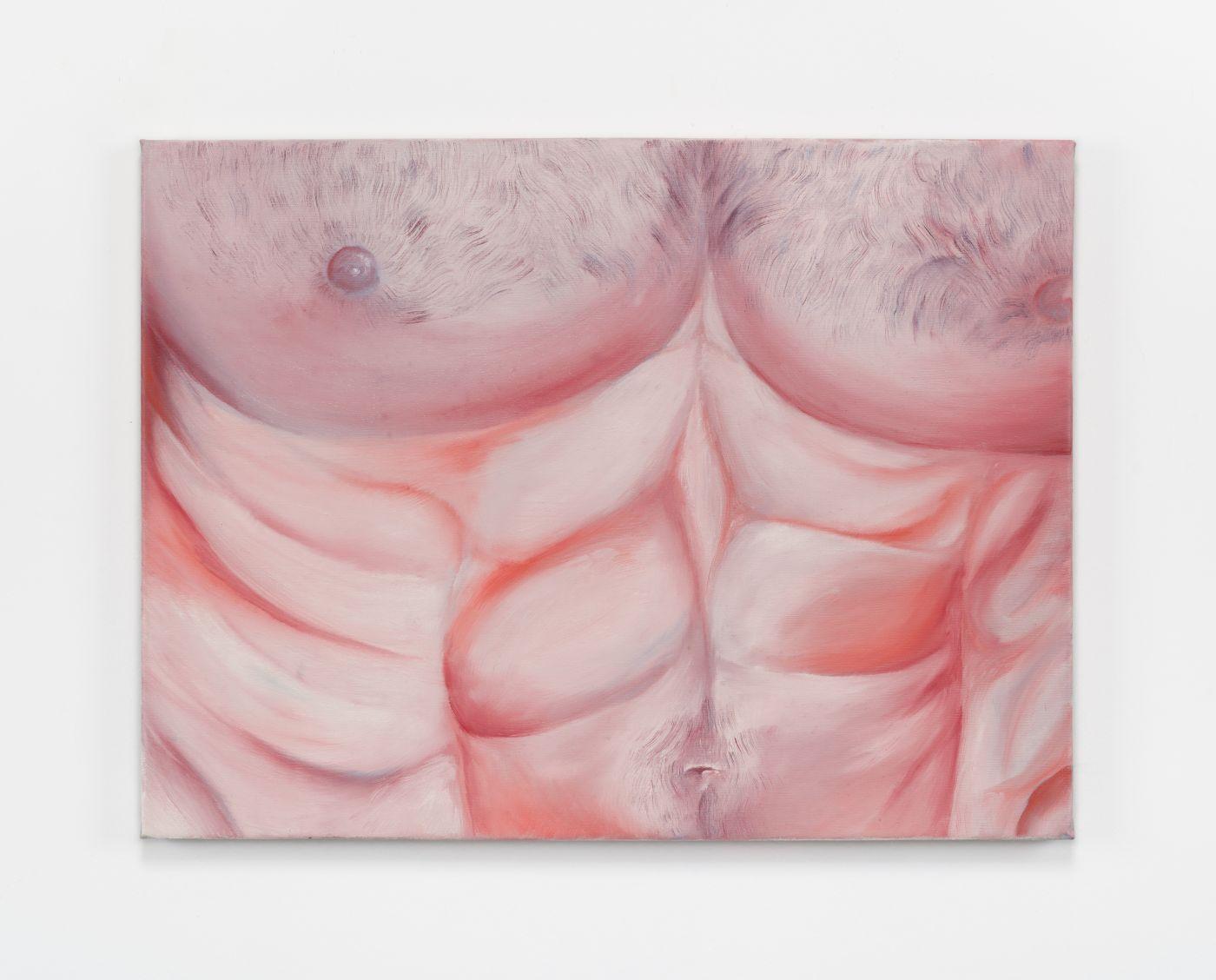

Rosalind Nashashibi’s Bachelor Machines

Men come together, men drift apart. They fix their eyes on one another or avert their gazes. Their bodies work together in concert, but their physical interactions are often triangulated by machines: scaffolding, a director’s dolly, a scrim, or a malfunctioning door hinge separate one man from the other. Sometimes, the camera—itself a machine—casts its gaze on them, lingering on the cicatrice on a sailor’s hand, the denimed pelvis of an Italian youth, or the pensive movements of a middle-class Englishman seeking intimacy amidst the foliage of London’s Hampstead Heath. These images center the movements of male bodies, but they are rarely erotically charged. Instead, they represent the efforts of a filmmaker, Rosalind Nashashibi, to both document and deconstruct a homosocial milieu that, as a woman, she is usually unable to access.

presented by Spike Art Magazine

For the next year, Spike is inviting authors from around the world to write a freeform exploration centered on an artist of their choice from the Liste Expedition universe, sharing insight into their works.

December 2022

Geoffrey Mak

Signs and wonders

Rachel Rossin is obsessed with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agencyan agency of the United States Department of Defense responsible for the development of emerging technologies for use by the military. “I like to keep up to date with what DARPA is doing,” she told me. “I like to figure out how to prepare myself for what’s coming.” We were talking about “stingrays” – briefcase-sized surveillance devices used by the New York Police Department to hack data, like phone numbers and call histories, from cell phones in the area by mimicking the functions of cell phone towers, which typically provide reception. During the Black Lives Matter protests, Rossin noticed that whenever a helicopter came close, her cell phone bars would go from one to four. As a self-taught hacker since she was a teenager, she wanted to know why: “I inverted the signal from my laptop, went through my phone, and got the MAC [media access control] address for this stingray. And sure enough, I saw where it was manufactured, and that the NYPD owned it.”

November 2022

Brit Barton

Smother to death, bring back to life

The 204 days it took to build the monumental reinforced-concrete block that covered up the nuclear site of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant were mired in a matter of semantics. Officials wondered what the site should be called, with the ultimate hopes of straying away from the death image and of quelling the global outrage with a strong, symbolic structure. In Russian, it became formally known as Obyekt Ukrytiye (“object shelter”), but it was commonly referred to as the “Chernobyl Sarcophagusespecially in the West and in international interviews for years to come” and it did little to aid in the Soviet reputation after the catastrophe – especially when it needed its own covering 10 years later. As the structure began to erode much sooner than the original 20-to-30-year shelf life that had been predicted, the Greek origins of sarco- as flesh and -phagus as eating became more relevant and recognisable, particularly as the USSR had also crumbled onto itself.

October 2022

Arnon Ben-Dror

All that was solid

“All that is solid melts into air.” Why do these words from the Communist Manifesto still give me the chills? Perhaps it is their uncanny prophetic quality, envisaging the dissolution of reliable systems of living long before our post-Fordist age. Or perhaps it is their poetic nature, so unlike Marx’s or Engels’s usual technical terminology. Or could it be the intriguing aesthetic – tactile almost – sensibility with which the German philosophers perceived the new reality we are facing? The age of capitalism, they presciently understood, brings about not only a new rationality but also a new sensorium – one lacking tangibility, stability, solidity. Today, in our “liquid” society as termed by sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, this prophecy seems more palpable than ever. De-solidification pervades almost all aspects of life, from relationships to identities to working conditions.

September 2022

Coco Klockner

Technical images, real abstractions

What am I looking at? I regularly return to such a reliable question when watching Vijay Masharani’s work. This isn’t because I don’t recognise the basic components of subject matter in each of his video works – they’re usually quite clear – but, rather, because such a question extends beyond describing the standard role of audience spectatorship; instead, the anti-cinematic approach Masharani employs in his austere videos stages scenery as if the camera itself is asking this very question, examining objects and situations slowly, expectant of some answer. In this equation, any audience asking this question finds themselves merely along for the ride as the camera’s eye asks its own questionsin real time. These images consist of defamiliarized quotidian scenes that all appear to be charged in some way, even if just for their inclusion: a walkthrough of an aquarium shop in Queens, New York, before encountering a racialised threat posted by the register (Good Attack, 2021); a CGI monkey clinging for its life on the side of a building (Mourning In Advance, 2021–22); a technical image of infrared-illuminated airborne droplets measured against a dark backdrop (Command | Plea, 2021); or an inverted image of an ornamentally lit motorboat whose reflection dances like a mirage on the surface of a nocturnal body of water (Nervosism, stutter, b-b-buh-bye, 2021).

August 2022

Isabella Zamboni

No way around beginnings, middles, and ends

“I believe every thing, object or person, is a translation from something or someone else,” Lynne Tillman once wrote, looking at “how history ranges and settles, seamlessly or roughly, in the present, […] how naming is usually re-naming.” This is from her text called “Drawing from a Translation Artist”, and I like to call Margherita Raso a translation artist, too. Raso is interested in what happens when things change skins, how information travels, and what is left or born anew when it does.

June 2022

Olamiju Fajemisin

Metapainting

Peering at the 13-inch screen of my laptop, I tap the “increase brightness” button until it reaches the highest setting and squint. Using my fingers to pinch and scroll, I zoom in on high-resolution images of paintings by Srijon Chowdhury so that I might imagine viewing them to scale. The works, all oil on linen, swallow my screen as I search their surfaces for traces of reason amongst the artist’s preferred motifs: Chiaroscuro, botanical devices, and naturalism command the scenes of this painted, metaphysical dimension. The images are wont to suggest a religious interpretation, though this is quickly realised to be an illusion projected by the sheer banality of each scene as Chowdhury imagines the contemporary through his mythic, Mannerist style. The artist was raised in the US and Bangladesh, where he was born in Dhaka to a Bangladeshi father and an American mother, and now divides his time living and working between Los Angeles and Portland, Oregon The simultaneous banality and significance of these details exemplify the question of subversion in Chowdhury’s work.. One might also describe his style as coming after miniature, or Mughal painting, which developed in the Indian subcontinent as royal patrons encouraged painters to assume the principles of the concurrent European art, producing highly detailed, pictorially flat images of histories across the personal, moral, romantic, religious, agricultural, royal, pastoral, mystical ….

May 2022

Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Flagged for lulz

!Mediengruppe Bitnik might just be doing it for the lulz. To present-day eyes and ears, this internet phrase is already an item of media folklore. Referring to a carnivalesque laughter rising from the depth of message boards, the term denotes both a specific historic context and a strategic positioning towards institutional power. The former has become understood through anthropologic studies of the hacker galaxy Anonymous Chronicled by scholar Gabriella Coleman in her eponymous study published a decade ago, Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous., and it also marks a global, generational awareness of internet-assisted activism. The latter, meanwhile, is a spirit and a strategy, symbolised through the persona of the lone trickster, jester or fool, which transcends mediatic regimes – one that, plunging its roots in the avant-garde practices of Dadaist outrage and Ubu-esque absurdity, resurfaces in sweeping waves at times of paradigmatic political change.

April 2022

Jaime Chu

Ad for America

In eight video segments that comprise Professional Witnesses (2021), eight actors in different roles as survivors of the 9/11 terrorist attack in New York each perform a monologue whose script has been culled from self-recorded video testimonies for the Voices of 9.11 archive, the official 9/11 Commission Report by the US government and interview transcripts of first responders from the report. Against the backdrop of an all-white studio with their mannerisms, stylised like an early-2000s TV advertisement citing Errol Morris’s “Switch” campaign for Apple, Benetton ads and the like, the “survivors” and the ruptures in their performances gradually corrupt the sanctity of the testimony. Narrative becomes suspect, and susceptible to judgment. From a distance, we can now see how certain claims to innocence have been foreclosed by the conspiracy between global commercial capital flow and national consciousness. When victimhood becomes compromised as performance, who stands to profit? How soon is too soon?

"Siskin or a speculative study on the possibility of a language of plants"

March 2022

Juan José Santos

March 2022

Juan José Santos

The league of the willows

A dot. A small, black, microbeam isolated over a white page from which language is born. Dot is also the surname of an artist whose work is materialised from words. Maybe all of this is a little too OuLiPo, a literary group cofounded by Raymond Queneau, the man who jumped the abyss between rigid written French and rough spoken French. It was Georges Perec, another member of OuLiPo, who said that to be totally free, you first have to establish some rules. In his autobiography, W, or the Memory of Childhood (1975), Perec wrote, “My family name is Peretz. It is found in the Bible. In Hebrew it means ‘hole’.” A hole through which words escape and where, in the end, only one point remains. Perec in Hungarian means pretzel by the way.

"Girl at heart"

February 2022

Chang Qu

February 2022

Chang Qu

Lo-fi home mix

A man abruptly shouting “lunch!” in the opening scene of Phung-Tien Phan’s Girl at Heart (2020) is just about the only indication of time in the video – or any of the three videos presented here, for that matter. Swiftly, the video takes a cheerful pace, intermixing photos of burning luxury sportscars with footage of a chef scoring squid from what seems like an Asian cooking show and a man sipping red wine in a cosy bistro, sound-tracked by upbeat erhu Chinese folk melodies paired with rapid chopping noises. Then it transitions to a wobbly handheld camera shot, tracing modern mouldings inside a clean, white-walled apartment. In a typical family kitchen, Mad Men plays on a laptop next to the stove. Accompanying the sizzling sound of tofu frying, Don Draper leers at colourfully dressed women on the street. Next, it goes to a mantelshelf, and outside to a boulangerie. It rotates past the window, the city spinning, the sun radiating. Following the light, it continues to wander through the city, a park, an empty street. Finally, it finds the artist, carrying a duffel bag that says “murder”, walking down a high street while in a stand-up-comedy-style voiceover she speaks about vintage fetishes and some of her mom’s crude jokes. The frying sound comes back. A Vietnamese pop song by Min cuts in. The end.

January 2022

Guilherme Teixeira

After a riffle shuffle, the cards cascade (or how we assist abandonments)

SIDENOTE: C. L. Salvaro’s studio/living space is an old house in the Jardins neighbourhood of São Paulo, where, alongside several images of the works presented at Liste, he has assembled a living installation. What may sound quite descriptive in the text that follows echoes Salvaro’s own work and its capacity to exist within an environment while questioning how a contemporary practice can unfold through, and with, the responsibilities of the space towards matter.

December 2021

Leila Peacock

Invocations and impressions of a place that is not a place

“Chance is the greatest novelist in the world: to be productive one has only to study it.” –Balzac

The series "Point No Point" (2020) comprises of five paintings. Three are landscapes, which hang unstretched and loosely depict a slice of rural coastline with what is discernible as a lighthouse on one side. The other two are hung, stretched, in portrait format, their forms echoing the structure and proportions of the coastline but flipped on its axis and left as a gravity-defying lattices of dripping pigment. Slipping between modes, Anne Fellner’s genre-fluid paintings draw us into an uncertain place between the act and the actual, where process, paint and perception all seem to play the role of protagonist.